Appraising Mamdani’s Five Key Policies

October 30, 2025

Zohran Mamdani, May 2025/Getty Images

The following guest blog is from Maliha Safri, Professor of Economics at Drew University, and co-author of Solidarity Cities: Confronting Racial Capitalism, Mapping Transformation, an examination of solidarity economies in New York and other cities. She is a volunteer canvasser for Zohran Mamdani. The views expressed are her own.

New York mayoral hopeful Zohran Mamdani’s policies can be enacted using past precedent in the city, as well as contemporary examples from other cities.

His policies are not only feasible, but they could work to improve the lives of a majority of New Yorkers who face housing precarity (68% of us are renters, with the majority facing crippling housing cost burden), food insecurity, the inability to afford childcare, and who suffer from the general feeling that our labor is getting sucked from us without letting us live decent lives.

NYC has a history full of amazing and successful municipal projects. These include a free city public library that debuted in 1911 as ‘the People’s Palace’ on 42nd street and Fifth Ave and the famous City College, which stood from 1847 to well into the 20th century as a place where the brightest and poorest kids in the city entered the tuition-free university. To many it was known by the popular title: Harvard of the Proletariat.

The NY City Housing Authority constructed hundreds of thousands of still-standing housing units, one of a spate of programs shaped by public investment in the New Deal. This period saw a range of programs address the housing crisis in the city, including public housing, the Mitchell Lama affordable housing cooperatives, and rent control measures. Amongst many prominent bottom-up and community-led struggles, a community garden network fought and won in the late 1990’s against then-mayor Rudy Giuliani, as he sought to raze these green spaces to the ground only to give the land to real estate developers.

Co-op City, Bronx, a Mitchell–Lama housing development, September 2007/Wikimedia Commons

These initiatives made the city better, because a city with skyscraper levels of inequality, without green spaces, without commons, is bad for all. Or, as Ruha Benjamin so eloquently wrote: “Whether you’re the explicit target or not, inequality makes us all sick.” As Benjamin points out in her 2022 book Viral justice: How we grow the world we want, the erosion of public services - public education, housing, healthcare - has led to the decline in life expectancy of the average U.S. citizen, including white Americans. “As it turns out,” Benjamin writes, “few can shelter from the weathering effects of a fraying social system, even those who happen to be ‘privileged’.”

So before you claim ‘socialism has never happened successfully,’ take a look back at many programs you might already be using that came out of a deep and wide wave of municipal policies advancing the common social good through expanding equity and affordability (often as a result of public pressure).

As the slogan goes, “NYC is a union town,” and that material reality forced the adoption of socialist policies advanced by a rebel citizenry in the 1930’s, 40’s, 50’s, and 60’s. The famously neoliberal period of the 1970’s was an assault on precisely this aspect of the city, with the first casualty being the sacrifice of City College as the nation’s elite and free university.

NYC has a past of incredible fights, and right now this city faces a fight and a fork in the road. Former New York governor Andrew Cuomo offers the status quo, but Zohran Mamdani’s program offers a chance to do the political economy of New York City differently, pulling from a glorious past, a present full of city-based activists and organizations already working on these problems, and an internationalist future.

What follows is a brief overview of five key policies, from easiest to enact to the hardest.

1. Rent freeze

The Rent-Guidelines Board is appointed by the mayor of NYC. Outgoing Mayor Eric Adams appointed people that allowed rent-stabilized apartments to rise in price by 9%. A new board can be appointed to actually freeze rents, and this can be done on day one. This measure is in the category of ‘easiest of all’ policies, that will nonetheless ripple out benefits for the 2 million New Yorkers living with some kind of rent-regulation. Just over half of renter households were rent-burdened in 2023—spending 30% or more of income on rent (with a majority of low-income households falling in the severely rent-burdened category). This one policy of rent-freeze would, of course, not solve that entire problem, but would be a step of many needed to cover all categories of renters.

City Comptroller Brad Lander had already petitioned for a 0% rent increase (i.e. a rent freeze) in April 2025 to the Rent Guidelines board, citing that the real estate sector reported an 8% increase in net income in the previous year. Just before Eric Adams, Mayor Bill de Blasio froze rents for three years in a row. And the history of rent stabilization measures in NYC goes back a long way. From the 1940’s through the 60’s, “rent control” measures were enacted by multiple administrations, and after 1969 there was a discursive shift to “rent stabilization.” But any way you slice it, there are a lot of NYC administrations that enacted rent capping measures to avoid predation in housing. Zohran wouldn’t be the outlier but a pretty average mayoral Democrat on this issue.

-

Landlords will likely be very upset and wealthy private real estate investors will invoke the specter of a small landlord losing profits (in the second mayoral debate Republican mayoral nominee Curtis Sliwa spoke continuously about the plight of small landlords being victimized in tenant courts). However, currently, 89% of all units registered with the Department of Housing Preservation and Development across the City list a corporate owner.

2. Public groceries

There is a vibrant food justice movement in NYC and beyond, struggling long and hard against food apartheid in the city. Many different people are working to get community gardens producing food in the middle of ‘food deserts,’ engaging in mutual aid community fridge programs, community supported agricultural farmers partnering to facilitate Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program access and adapting to immigrant diets, and so much more.

These activists should be drawn on as a politically-committed, already-knowledgeable labor force and think tank for a public grocery system. One of many potential partnerships between activists on the ground can be seen in how Brooklyn Packers has been thinking about the production of a city-wide systemic effort to address food justice by coordinating grant-making across the city and sharing resources across BIPOC and Queer farms, and facilitating access to food in multiple NYC communities of color.

There are already city-owned groceries in the United States in Madison, WI, and St. Paul, KS. The Madison Grocery opened in a city-owned project that also includes 150 units of affordable housing. There are plans for 3 city-owned groceries in Chicago at the cost of a $26 million investment, and Atlanta is opening one next year. All these cities are opening municipally-owned groceries in neighborhoods with high concentrations of poverty and people of color, with very little to no access to fresh food. Private grocers operate on the basis of profit, and overserve wealthier neighborhoods while underserving lower income ones. Atlanta Mayor Andre Dickens commented exasperatedly as he was trying to address the city’s food deserts: “We’ve reached out to grocery chains and even offered incentives — no takers,” adding, “So we will make it happen for the people directly”.

With modest investments into 12 municipally owned groceries at a few million dollar investment per site, NYC could become the first major city to not just talk about food inequality, but move substantively towards an urban-level solution. We always needed a new system to counter a systemic problem.

-

The grocery would run as a municipal non-profit, so groceries would be priced lower than market options, but not free. These markets would however accept SNAP and WIC benefits, which private grocers can choose to not accept despite their receipt of tax subsidies.

-

The new administration could find publicly held land and properties, especially in neighborhoods without food access, so costs could be kept low and ecologically more sustainable by refitting existing structures. But there are grocery stores also for sale, including one with a five-year lease on bizbuysell.com in Brooklyn listed for $450,000 on July 20th, 2025. Inventory for that 2700 sq ft store came to $150,000, with $300,000 in investment into necessary equipment (refrigerators, freezers, ovens, scales, registers, etc.). If converting city-owned properties (see fascinating Atlanta community land trust model for grocery plus affordable housing complex for how to retrofit rather than construct anew), then the grocery could save the approximate $10,000 in rent per month for the above Brooklyn grocery for sale.

3. Childcare

NYC already has a money voucher program in place for families with children from six weeks to 13 years old. This voucher system is designed to help qualifying families on low incomes, given the high cost of childcare. In 2025 the program saw a first-time increase since the 1990s, with $350 million coming from the state, and $220 million from the city. This includes a $10 million pilot program making childcare free in high-need neighborhoods.

Many two-income families leave the city when having their first baby because they simply could not make family-life work in the city any longer. Baby showers are often the beginning of a ‘countdown for departure’ betting game among friends. Not addressing this reality will lead to demographic imbalances in the city in the long term, creating a variety of social issues that will be harder and potentially more expensive to address than offering free childcare for all.

-

Mamdani’s plan to provide free childcare to all children from six weeks to five years old is merely broadening an existing program serving lowest-income families, extending it to all families instead. The policy has received explicit support from New York Governor Kathy Hochul.

4. Free buses

NYC has already tried a free bus scheme in the form of a one-year pilot program sponsored by Mamdani and state Senator Michael Gianaris in 2023. It included one free bus route per borough. The results were overwhelmingly positive. The Metropolitan Transport Authority (MTA) reported a 30% ridership increase across all the free routes and assaults on staff were a statistically significant 30% lower than average for all bus routes. The only downside was a slowing of speed since some riders diverted from paid routes specifically to take the free bus. Though this finding clearly indicates a problem with the systemic unevenness of the policy, not an inefficiency of the policy itself.

Policy analyst and economist Charles Komanoff modeled the city-wide application of the scheme and forecast a 23% increase in ridership, with an ultimate decrease of 12% of time spent in transit by riders. The benefits ripple through to drivers of private cars, with less traffic on the roads. What is more, right now the bus portion of the MTA brings in approximately $600 million, with rates of fare evasion much higher than the subways. Komanoff estimates this fall in revenue would be offset by an approximated $1.3 billion in multiplier-effect benefits in the local economy.

-

Transit Workers Union (TWU) President John Samuelson said during his Labor Day speech he was “absolutely” in favor of the free bus fare scheme. Earlier this year he stated that “every mayoral candidate thinks they know something about public transit, and they don’t know shite. But Zohran reached out, talked to the workers, talked to worker leaders, and he’s firm in his understanding of what working people, riders, and New York City transit workers need to make this system better.”

5. Affordable housing

Zohran’s plan is to construct 200,000 new units of permanently affordable, union-built, rent-stabilized homes – over the next 10 years. We have been here before. Back in 2014, Bill de Blasio also sought to create 200,000 of affordable housing in 10 years. And de Blasio did it. Problem was, 200,000 was really a drop in the bucket.

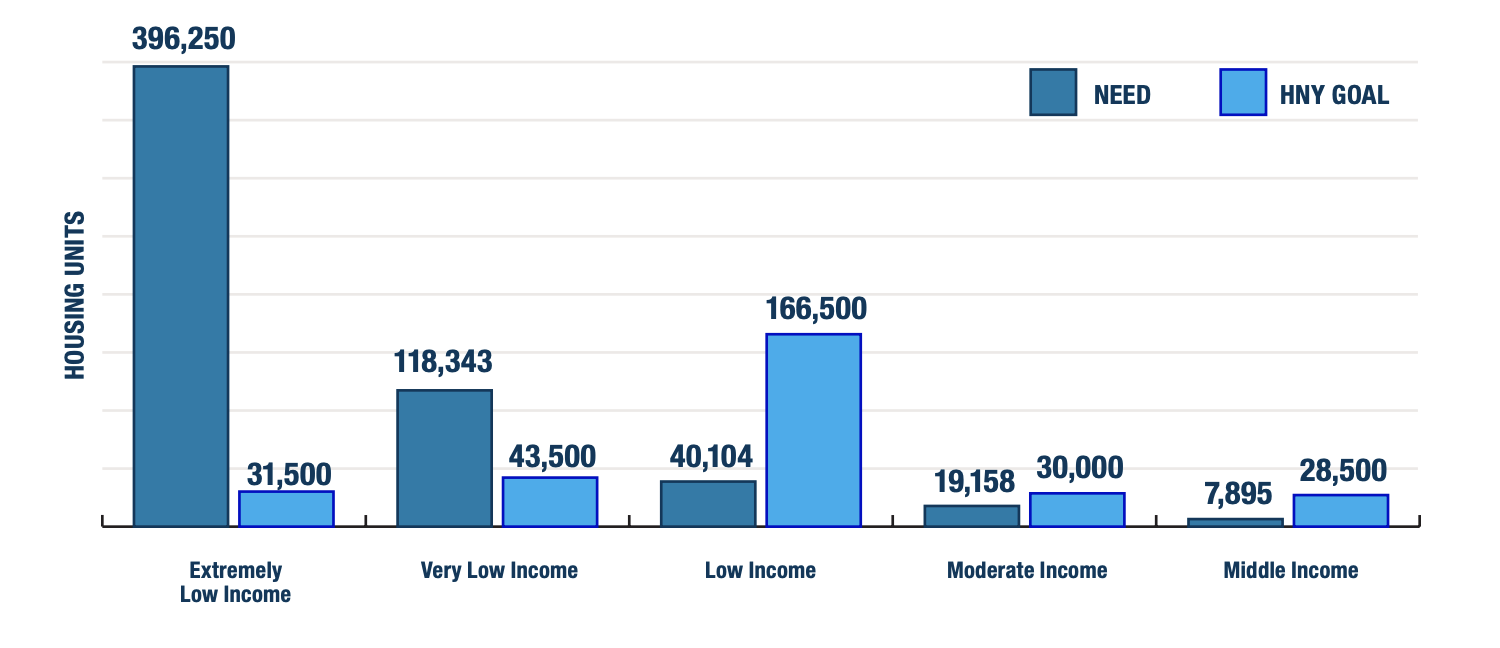

Analyst Samuel Stein’s appraisal of housing under the de Blasio mayorship depicts a distribution across income categories. Stein’s work shows how the goals of the Housing New York program fell substantially short of the units needed amongst the Very Low Income and Extremely Low Income groups. It fell nearly 440,000 homes short, in fact.

For Mamdani, the difficulty will not be in pulling his housing policy off, but in ensuring access to it by those in deepest financial stress and rent burden. Additionally, he will have to keep building affordable housing because, as Stein’s report showed, 200,000 units will still not solve the problem.

Housing policy should be part and parcel of a commitment that runs across mayoral administrations not to be solved by a single mayor, even if Mamdani’s plan comes to fruition. There should be a long-term plan to use public money to build affordable housing, that will necessarily involve state support.

-

Keeanga Yamahtta Taylor’s work on the post-1960 history of US housing has shown that the private sector will never actually build affordable housing at cost for low-income people. The private sector (as in the case of food deserts) seeks more profit by overserving the wealthy rather than the low-income. Even when the government designs voucher programs, those programs end up subsidizing private landlords more than low-income renters.

In Conclusion

The answer to a fascist turn in politics cannot be to try and make the Democratic Party more like the GOP, like some NY mayoral candidates seem to think. Bold policy ideas can come from a working-class politics that don’t simply entrench the worst aspects of racial capitalism. Zohran Mamdani’s key policies embody some of that spirit.

About 90,000 volunteers came together behind Mamdani to hopefully be the start of something new in NYC, that is of holding power accountable to promises of repairing social welfare programs; and form a vibrant and diverse civil society that works with and against the state when necessary. Mamdani might not be the solution to every New York problem, but he is the only candidate offering a paradigmatic shift from a city run by corporations to a city run by we, the people.

To my fellow volunteers working so hard even in this last stretch, our work might soon enter a new stage, but cannot end on election day.